"If you see us publishing someone you will know that they are profitable."

Marjorie Scardino, CEO of Pearson, owner of Penguin books, quoted in today's Guardian.

Tuesday, February 28, 2006

Whaddya know?

The Know-It-All, by A.J. Jacobs (Arrow, 2006)

The Know-It-All, by A.J. Jacobs (Arrow, 2006)It seems to be a fairly common symptom of the early mid-life crisis in the Western male; a gradual acknowledgement of one's own cultural inadequacy and laziness. Part of the reason I started this blog was to keep track of what exactly I was watching, reading, listening to; and also to force myself to consume the cultural slushpile with a little more critical rigour than I'd been applying in recent years. If I know I'm going to write a few hundred words about something, I'll pay more attention.

A.J. Jacobs, an editor at Esquire, had similar feelings of intellectual insufficiency, and decided to remedy them. He was a bright boy, possessed in his teenage years by the hardly unique assumption that he was the smartest kid in the world. Once he started writing about celebrity dross however, he lost his intellectual compass a little, and forgot a lot of the important stuff. So he began reading the Encyclopaedia Britannica. Not consulting the damn thing, note; reading it. A to Z.

It's an impressive task to set oneself, but immediately the car alarms go off in the street outside. Pardon my cynicism, but why would a journalist (especially a male journalist in his mid-30s, who's doing OK in consumer mags but isn't really perceived as an author as such) do such a thing? To write a book about it, maybe? So, from the start, the purity of the quest is compromised. He's doing this for the same mixed motives that persuade Bill Bryson to go on long walks; it's good for you, but it also provides material. Jacobs' NYC Jewish schtick provides the rest, with a few dashes of Nick Hornby, P.J. O'Rourke and maybe Bryson himself.

That said, it's a good idea, and provides a handy structure to the book. Jacobs starts on 'A', and you know (at least, you hope) he'll make it past 'Zola' by the time the story ends. En route, he uses the various entries as hooks upon which he can hang amusing nuggets of trivia (very Bryson); and also recounts various family anecdotes, as well as the saga of his and his wife's fertility traumas (hello Hornby, or if we're in a sour mood, Ben Elton). In addition, he meets various Mensans and other bright folk, ponders the distinction between 'intelligence' and 'knowledge', and applies to go on Who Wants To Be A Millionaire?

The devil, however is in the details. At this point, Jacobs would tell you, in a mock-casual aside, who coined that cliche. Or would he? As you follow his journey of 44 million words, you start to wonder.

For example, many of the nuggets by which he claims to be astonished are, surely, pretty run of the mill stuff, especially when one considers that he's a hack specialising in pop culture. Rene Lacoste was a top tennis player before he became a sportswear mogul. The Lumiere Brothers made the first real motion picture. Madonna's middle name is Louise. Coriander and cilantro are the same thing. Nobody is really sure how the Oscar got its name. Rasputin was poisoned, shot and stabbed before being pushed through a hole in the ice. This is all stuff that would scrape a 'C' in the trivia GCSE. Semi-serious pub quizzers would laugh with derision if these arose during a match. Jacobs had never even heard of Kool Herc, the man who has as much claim as anyone to have invented hip-hop; but at least he has the grace to be embarrassed by that one.

What's worse, with this massive work of reference at hand, is that there are straightforward goofs here. Avogadro (of number sequence fame) and Sartre (of pipesmoking existentialism fame) get their names misspelled. Trotsky, we learn, was killed "by an axe murderer". No, it was an icepick; not a distinction that would have bothered the former Mr Bronstein, but a fact known by such polymaths as The Stranglers and Salma Hayek. The "ae" in the book's title is ascribed by Jacobs to "apparently Greek-inspired spelling". Well, no, that's just how "encyclopaedia" is spelled in British English.

Indeed, Jacobs' grasp of cultures beyond the boundaries of the United States seem shaky to say the least. His encounter with Miscellany maestro Ben Schott (Jacobs goes tooled up with a few factoids on how the two Englishes differ) is a masterpiece of discomfort and embarrassment. Schott, of course, knows that fruit machines are also called one-armed bandits; for Jacobs, the fact that one-armed bandits are also called fruit machines is an eye-opener of Darwinian proportions.

I hate to make generalisations, and I apologise to any inhabitants of the former colonies here, but is this something to do with Jacobs being American? You see, in many ways, I'm very similar to him: same age, Jewish, middle-class but slightly bohemian upbringing, pissed away university, ended up in publishing, realise we don't know enough important stuff. But it's only when he starts talking about baseball that I feel myself bowing to his superior knowledge. And even I knew that baseball was originally derived from rounders, which was news to Jacobs.

I know there are plenty of well-rounded, inquisitive Americans out there, as well as Brits whose cultural blinkers snap down as soon as the Eurostar leaves Waterloo. If you're offended by my crass oversimplifications, and want to pick up on any egregious goofs that I've made, please post away. But, as Richard Lewis put it, we know more about you than you know about us. Perhaps the most appropriate conclusion should have been a consideration of the very nature of the canon of knowledge, and how it influences what goes into Britannica. Is there a Western or American cultural bias? A class bias? Is it right that the editors should take the long view on inclusion, to avoid the crass neologisms that fill the press releases whenever a new dictionary appears? There's serious stuff to chew on here, and Jacobs doesn't think of going there. He'd rather be nice to his wife. Aaaaahhhh.

There is, however, one really neat sliver of triv that was new to me. Did you know that Alaska is the most northerly, most westerly and, because of the Aleutian islands crossing the 180th meridian, most easterly of the American states? But that gem comes from Jacobs Senior, apparently a delightful practical joker who would probably have written a better book than his son has.

Monday, February 27, 2006

Jesus' blood never failed me yet

From the website of Richard Leigh, co-author of The Holy Blood And The Holy Grail:

"Richard Leigh has recently completed a novel, tentatively titled Grey Magic, in which an antinomian hermetic numinist confronts the conflict between artistic detachment and political commitment set against the turbulence of the Civil Rights Movement in Mississippi, the Vietnam War, and the troubles in Northern Ireland."

Hmm, I can see publishers trampling each other in the rush.

Incidentally, Mr Leigh and one of his colleagues are suing Dan Brown, author of the moderately succesful The Da Vinci Code, for plagiarism, because he "stole their idea that Jesus had a child". Since Leigh claims that The Holy Blood is factual, I'm not entirely sure what he thinks he's doing. If you put an intellectual idea in the public domain, claiming that it's (sorry) gospel, don't you want as many people as possible to agree with it? Isn't this case a bit like Matthew and Mark suing Luke and John?

Update, Mar 1: Go here for further discussion. Much of which is suspiciously similar to the above. Which doesn't necessarily prove plagiarism of course - could be that my original thoughts were entirely banal and unimaginative. Which is my whole point, really.

"Richard Leigh has recently completed a novel, tentatively titled Grey Magic, in which an antinomian hermetic numinist confronts the conflict between artistic detachment and political commitment set against the turbulence of the Civil Rights Movement in Mississippi, the Vietnam War, and the troubles in Northern Ireland."

Hmm, I can see publishers trampling each other in the rush.

Incidentally, Mr Leigh and one of his colleagues are suing Dan Brown, author of the moderately succesful The Da Vinci Code, for plagiarism, because he "stole their idea that Jesus had a child". Since Leigh claims that The Holy Blood is factual, I'm not entirely sure what he thinks he's doing. If you put an intellectual idea in the public domain, claiming that it's (sorry) gospel, don't you want as many people as possible to agree with it? Isn't this case a bit like Matthew and Mark suing Luke and John?

Update, Mar 1: Go here for further discussion. Much of which is suspiciously similar to the above. Which doesn't necessarily prove plagiarism of course - could be that my original thoughts were entirely banal and unimaginative. Which is my whole point, really.

Sunday, February 26, 2006

Side by side on my piano keyboard

Manderlay (Dir: Lars von Trier, 2005)

Manderlay (Dir: Lars von Trier, 2005)In Lars von Trier's sequel to Dogville, we find Grace and her gangster father escaping the carnage of that Brechtian backwater. In Alabama, they stop outside a crumbling mansion, and Grace is asked to prevent the beating of a slave. But it's the 1930s, and slavery was supposedly abolished 70 years before. Intrigued and appalled, Grace decides to take action, but discovers that the black workers aren't exactly unwilling participants in this social timewarp. She ends up questioning her own liberal instincts and eventually, her deepest desires and motivations.

Von Trier continues the uncompromising Verfremdungseffekt of the previous movie. The action clearly takes place in a studio; cars drive across a vast map of the USA; walls and doors and running water are mimed. The alienation continues in the casting; Grace and her gangster daddy are reincarnated, Dr Who-style, as Bryce Dallas Howard and Willem Dafoe. However, half a dozen actors from the previous film (including Lauren Bacall and Chloe Sevigny) do make the transition - albeit as new characters. A further jolt comes from the fact that most of the black characters are played by British actors, many of them familiar TV and theatre faces.

Although the nominal subject matter is the ongoing racial rift that obsesses American discourse, the ideas thrown up here are much more diverse. Iraq for one; is it right, or even possible, to impose democracy on a culture that hasn't asked for it? Indeed, is democracy such a wonderful idea anyway? I saw the film in Thailand, a couple of days after the Prime Minister had called a snap election to deflect attention from his questionable business dealings. For various reasons (a fragmented opposition; a cowed media; rampant corruption and vote-buying) he'll win. But that's 'democracy'. Kinda.

But von Trier then sabotages this wider resonance with the end titles, a montage of images of American racial conflict. It's brilliantly done, to the sound of Bowie's 'Young Americans', but it refocuses the viewer's attention on a specific socio-political problem, rather than opening the argument up. Hollywood's done plenty of navel-gazing over The Race Thing, from Birth Of A Nation to Crash. It's a big story, but it's not the only story.

Manderlay is meaty, adventurous film-making, and will inspire earnest debate over the popcorn dregs. But von Trier should have followed Brecht more closely. Old Bert's at his best when he's dealing with the big subjects, war, corruption, exploitation, rather than the specifics of his own time and place. Lars has nearly made a movie of truly global significance, but blows it in the last few minutes.

Saturday, February 25, 2006

People who'd have given their bands a different name if they'd started out in the era of search engines

Out to lunch

The Sex Pistols, a middle-aged beat combo, have announced that they will not be appearing at their induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, calling the institution "a piss stain".

Susan Evans, executive director of the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame Foundation, responded: "They're being the outrageous punksters that they are, and that's rock 'n' roll."

PUNKSTERS???

Susan Evans, executive director of the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame Foundation, responded: "They're being the outrageous punksters that they are, and that's rock 'n' roll."

PUNKSTERS???

Friday, February 24, 2006

Anachronesis in pieces

I'd rather Jacques

Jacques Brel Is Alive And Well And Living In Paris (Dir: Denis Heroux, 1975)

Jacques Brel Is Alive And Well And Living In Paris (Dir: Denis Heroux, 1975)When I was in London last week, I couldn't help noticing how many of the West End theatres had been occupied by shows that are essentially content-free. Unless, of course, the concept of "content" has been extended to include pretending to be Dean Martin for a couple of hours, or stamping a lot while wearing a vest. Or blue face paint. Or all three. Some have explained this process as part of the globalization of entertainment, or as the function of commercial theatre as an arm of the tourist industry. Essentially, if a coach party of Korean tourists aren't going to understand it, it's not going to be viable.

At the same time, it's a sneaky way of following the official line that theatre and other manifestations of 'The Arts' should be made 'more accessible' - in this case, to people who find the plots and characters of your average Lloyd Webber show excessively challenging. So you either ditch story and dialogue entirely, or make sure that any narrative is buttressed by plenty of tunes, preferably ones that the audience has imprinted on its collective DNA already. The logical end of this is Dancing In The Streets, essentially a live-action, Motown version of Stars In Their Eyes with amusingly bad wigs.

Of course, this isn't a new thing. The content-free musical dates back at least to 1968, when a show called Jacques Brel Is Alive And Well And Living In Paris (which the Belgian troubador was at the time) opened in Greenwich Village. Seven years later, the show was committed to celluloid at the behest of the American Film Theatre, an outfit that believed it was making permanent records of theatrical masterpieces (rather than straightforward film adaptations) because, uh, it had 'Theatre' in the title. And because it paid the actors rather less than they'd get for making movies.

The main impetus behind the original show was Mort Shuman, who also performed on stage and in the film. The main obstacle to Brel's acceptance in America was that he had the bad taste to write and sing in French (and occasionally and even worse, in Flemish, which Americans not only couldn't understand, they'd never heard of it). So Shuman, being a talented soul (he had, after all, had some success in partnership with the with the obese, crippled blues shouter and professional gambler Doc Pomus, penning 'Save The Last Dance For Me' and, uh, 'Viva Las Vegas') gave the songs English lyrics that reflected Brel's bleak, laconic romanticism.

Crucially, what Shuman didn't attempt to do was to hang a plot around these vignettes of Parisian lowlife. So, instead of a Rive Gauche Mamma Mia, we get barely connected performance pieces, with images and general actorly schtick that relate vaguely to the songs in question, but don't add up to any kind of coherent narrative. So we get signifiers of doom (whores and bullfighters and soldiers) and death (funerals and cemeteries and crucifixions) and off-Broadway theatres (puppets and pierrots and very bad mime ensembles). Also, we must remember that this was made in the 1970s, so backcombing and bubble perms are the order of the day. Shuman himself resembles Dom DeLuise in a Mick Hucknall hairpiece. Tasty. And there's a bit of product placement for, of all things, Damart.

The overall effect is of late-period Bunuel, all deadpan bourgeoisie doing ever-so-slightly absurd things. As the main female performer Elly Stone, puts it, they are all "surrealist pilgrims, melting clocks in marble halls". And bless her wonky teeth and hairy nostrils, it's so true.

All the poncing around is put into context when Brel himself appears in a bar, beer and cig at hand, and sings 'Ne Me Quitte Pas' without a crucified bullfighter in sight. Of course, he's the best thing in it. Sadly, in amongst all the wacky tableaux, they don't have room for his 'Le Moribond', possibly because Rod McKuen had beaten Shuman to that one, turning it into the magnificently sappy 'Seasons In The Sun'. It had topped the charts for Terry Jacks the previous year, and was thus insufficiently off-Broadway to satisfy the chin-stroking connoiseurs of sophomoric surrealism. Although, in the disjointed cobbling-together of music and image, JBIAAWALIP has left one legacy to mass entertainment - it pretty much invented the pop video.

Apparently, the show is about to return to the American stage, although since ol' Jacques ceased to be alive or well in 1978, the title may no longer be apposite. And I bet all the performers will be asked to shave their nostrils.

Wednesday, February 22, 2006

The final word on those bloody Mohammed cartoons?

Maybe. Check out the anti-semitic cartoon competition. Oy, and in a very real sense, vay.

Soft rock

Belle and Sebastian: The Life Pursuit (Rough Trade, 2006)

Belle and Sebastian: The Life Pursuit (Rough Trade, 2006)The songs of Belle and Sebastian sound familiar without it ever being quite possible to pin down what it is they sound like. Sometimes, of course, they sound just like other B&S songs, so that opener 'Act of the Apostle' pits Stuart Murdoch's airy tones up against Chris Geddes' jazzy electric piano, the same juxtaposition that made 'The Boy With The Arab Strap' so damn catchy. Other familiar motifs are present: the 'Legal Man'-style everything-but-the-kitchen-sink single ('Funny Little Frog'); the lugubrious Mick Cooke trumpet solo ('Dress Up In You'); and, of course, the title that can only be B&S (in this case, 'Sukie In The Graveyard').

But their palette is bigger and brighter than that, as is their collective palate; what's always kept them going is the tension between their "hello-trees-hello-flowers" whimsy and hard-headed rock 'n' roll encyclopaedophilia. They can lurch from the 70s pop-boogie-stomp of 'The Blues Are Still Blue' (a shotgun wedding of Chicory Tip and Middle Of The Road) via 'Song For Sunshine''s jolly jazz funk and on to the pounding beat of 'To Be Myself Completely', which could have filled the floor of the Wigan Casino. In fact, few acts have been able to ape so many diverse musical styles so expertly and with so little apparent effort since The White Album.

The band's wondrously eclectic jukebox is impressive but, as ever, it's the words that bite hardest. "She's a Venus in flares and you wanna split hairs!" ('The White Collar Boy'); "My Damascan Road's my transistor radio" ('Act Of The Apostle II'). And when the jokes get too painful, Murdoch is happy to acknowledge the fact: "Another sunny day, I met you up in the garden," he trills. "You were digging plants, I dug you, beg your pardon."

Possibly acknowledging B&S's literary bent, the CD is packaged like a mini-book, with a proper spine, and Q&As spawned by the band's fans and foes (Barry the man: "Why are you all so fucking gay?") in a neat little attached booklet. All, of course, in good-quality matt paper, not the shiny crap the band's lesser rivals use. I'm always dumbfounded that so many publishers of print media fail to realise the aura of quality that a matt finish gives to their product. It's like film stock over video.

At least Paul Whitelaw has taken the hint in his biography, Belle and Sebastian: Just A Modern Rock Story (Helter Skelter). It's a nicely constructed hardback, with the page edges artfully torn so the book resembles a roman that Jean Seberg might have picked up at a newsstand at the Gare du Nord. (With the cash she made from selling the Herald Tribune, of course ...sigh...)

At least Paul Whitelaw has taken the hint in his biography, Belle and Sebastian: Just A Modern Rock Story (Helter Skelter). It's a nicely constructed hardback, with the page edges artfully torn so the book resembles a roman that Jean Seberg might have picked up at a newsstand at the Gare du Nord. (With the cash she made from selling the Herald Tribune, of course ...sigh...)The book is an official version, to the extent that Murdoch gets credit for designing the cover, and Whitelaw is at pains to torpedo the lazy myths about the band; chief among them that they're fey, twee lightweights. The head Belle's love for prog behemoths Yes, not to mention his fondness for football, should kill those. Although the original name of his band's first incarnation - Lisa Helps The Blind - is just too cute for reality.

In fact, they're a pretty hard-nosed bunch all round, determined to play the music biz game by their own rules; when they started out, they avoided playing live, doing interviews, even being photographed. Their 1999 Brit Award (for Best Newcomer, around the time of their third album) could have been a springboard for massive commercial success; but they were in the studio, making their next record, so that was that.

This toughness may be a reflection of a little-known facet of the band that Whitelaw unearths; several of them had an academic leaning to the sciences, surely a rarity in pop circles, Brian May's astronomy obsession notwithstanding. Mick Cooke was set to be a pharmacologist; Chris Geddes was a physicist; as was Murdoch himself, before being sidelined by chronic fatigue syndrome (and there's a stereotypical B&S disease if ever there was one). How that scientific bent coexists with the leader's equally incongruous Christian beliefs is another matter.

Unfortunately, Whitelaw seems have been over-influenced by the early B&S, and the priority they gave to charm over getting the notes in the right order. Sometimes he just displays the need for a decent editor, or even a spellchecker. The dodgy vol-au-vent that floored Mick Cooke at the Brits doesn't have a 'Z' in it; and what is this 'Kassenatz-Katz' of which you speak, sir? More significantly, after tracing in meticulous detail Isobel Campbell's progressive disillusionment with band life, he places her eventual ship-jumping a whole year earlier than it actually happened. Incidentally, this sub-saga does produce one of the best quotations in the whole book, when Isobel justifies her dislike of touring thus: "You're always fishing around for things in your suitcase, it hurts your back."

It could well be argued that a rigorously proofed and fact-checked biography would be anathema to what Belle and Sebastian stand for; that what Whitelaw provides is nuance, feeling, passion, rather than sterile truth. After all, most fans would argue that the ramshackle debut Tigermilk is better than the overproduced, overwritten, infinitely more expensive Fold Your Hands Child, You Walk Like A Peasant. But following that logic, the story should have been written by Sarah the violinist in purple felt-tip on the back of a postcard of Julie Christie in Darling and mailed to each and every one of us. This may be "just a modern rock story" but surely it's worth getting it right.

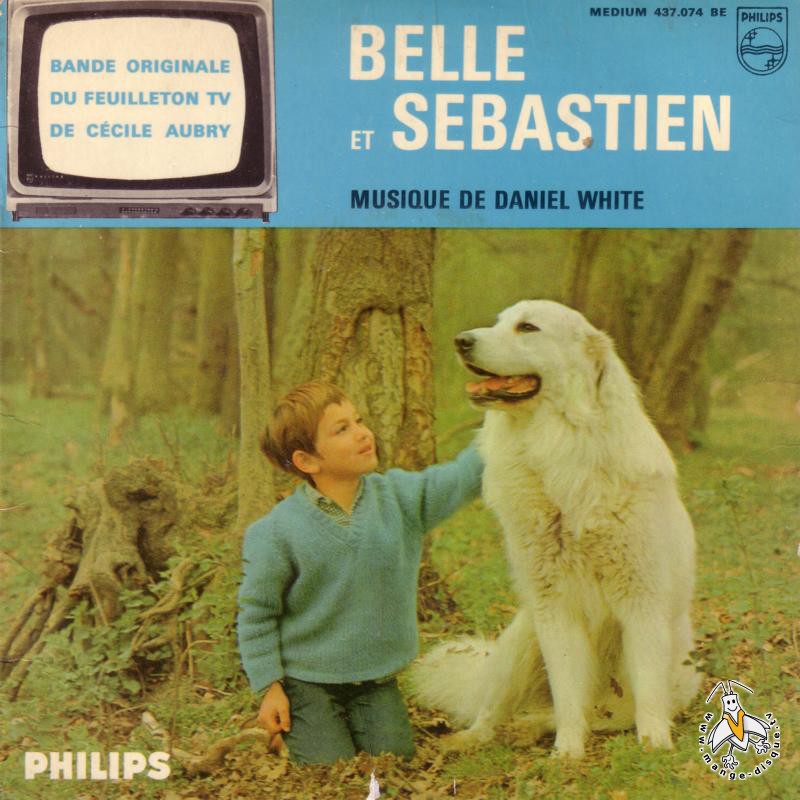

To his credit, Whitelaw does provide value for money, providing an exhaustive discography, plus a list of every cover version B&S has performed. Again, many of the choices dispel the 'twee' pejorative; they include 'Problem Child' by AC/DC, Lynyrd Skynyrd's 'Sweet Home Alabama' and 'The Boys Are Back In Town' by Murdoch's other raawwk idols, Thin Lizzy. Meanwhile, although they've tackled the 'Gallery Theme' from Vision On, those staples of the indie-cutesy repertoire, the tunes from the TV shows White Horses, Rupert, not to mention Belle et Sebastien itself, are absent.

Now available on DVD, this French-made 13-parter was a mainstay of summer-holiday BBC viewing in the '60s and '70s. Or was it? I can remember White Horses, of course, and also The Flashing Blade and The Magic Roundabout, but this one stirred no primal memories of sunny days, mivvis or white dogshit.

No matter. It's the tale of the Pyrenean mountain dog Belle, who is condemned to death by the inhabitants of a village in the French Alps, and of Sebastien, the child who is determined to protect her. It's in black and white, of course, and with its clunky titles and clunkier dubbing (English in French accents!), it's easy to see the ramshackle charm that first endeared the show to Stuart Murdoch. (Belle and Sebastian - the band - dutifully thank the show's createur, Cecile Aubry, on their album sleeves.)

But its indie credibility goes deeper. The protagonists are both outsiders. Sebastien is a foundling, whose mother died in a blizzard, leaving him in the care of the villagers. He's routinely bullied for his 'gypsy' origins; moreover, he is named for the saint on whose day he was found, the epicene icon whose arrow-studded suffering so entranced Oscar Wilde. Belle, too, is cast out of society for her alleged violent tendencies; and what's a Pyrenean doing in the Alps anyway?

As with so much Camusian existentialism, it's very much artifice. Medhi, the boy who plays Sebastien, was Aubry's own son, and appears to have had first refusal on all her subsequent shows. He later went on to be a big player in the French pharmaceutical industry. The Mick Cooke de ses jours?

And in case B&S decide to be unpredictable by being entirely predictable, the closing song 'L'Oiseau' (performed over the credits by Medhi) can be found here. Solo spot for Sarah, perhaps?

Tuesday, February 21, 2006

...unquote

"People in life quote as they please, so we have the right to quote as we please. So I show people quoting, merely making sure that they quote what pleases me."

Jean-Luc Godard, 1962

Jean-Luc Godard, 1962

Sunday, February 19, 2006

An incubus in Pimlico

Gothic Nightmares, Tate Britain, London SW1

Apparently, when the Sisters of Mercy tour these days, promoters aren't allowed to use the word 'Goth' in the publicity material. It's a sign that the last great Gothic revival, in which snakebite and black replaced laudanum, is finally mouldering in its prepaid plot in Whitby graveyard. But now the gallery that we old farts still call "the real Tate" looks set to kick off a new one, with an overview of the fascination for gloom and ghouls that possessed Britain in the late 18th and early 19th centuries.

The cornerstone of the exhibition is 'The Nightmare' by Henry Fuseli (1741-1825), who now joins my select list of famous Swiss people*. The image, of a gurning incubus crouching over a white-clad maiden, seemed to capture some sort of Weltanschauung, as the middle classes became obsessed with the more sordid facets of the supernatural, and also deviant sexuality. Not only did Fuseli keep returning to the image in paintings and etchings, but every other artist and his dog elected to borrow the idea. James Gillray, a cartoonist who makes Martin Rowson seem about as savage as Norman Rockwell, used the concept to lay into his political foes, the Prince Regent (later George IV) and his crony Charles James Fox. Fuseli, meanwhile, was diverted into doodling pornographic cartoons for the same prince, some of which are displayed at the Tate behind a discreet gauze. (Matron! The screens!)

Of course, Fuseli wasn't the only artist responding to the Walpolian weirdness in the air. His influence is seen most readily in William Blake, who took this thread of Gothic weirdness and grafted it onto his transcendent Albion, with its nice/nasty cop God. The exhibition also takes us on to early cinematic manifestations of the genre, such as Nosferatu and The Cabinet Of Doctor Caligari. The direct precursor to these is the Phantasmagoria, a selection of moving projections on a black background; disembodied heads, ghost riders, sprites, playing games with perspective and peripheral vision and our minds.

What particularly comes through is the range of literary references that crop up in the pictures. Milton, Shakespeare, and Dante are all over the place, as is Spenser. But we also get the likes of Undine, the Niebelungslied, even the Gaelic myth of Oscar (nah, me neither). When there was no cultural allusion available, the deeply committed artists (mainly Blake) made up their own. Presumably, these tropes would have been immediately apparent to the gallery punters of the day, which seems to imply some sort of common "high" cultural heritage (at least for the middle classes) that's now lost. Or have hypertext links replaced a common code of aesthetic indicators? Or should I assume that all readers here know who Martin Rowson is, and what the hell Weltanschauung is when it's at home? Indeed, should I have left those links off, and linked to Milton and Shakespeare instead? When the minister for higher education says that it's no bad thing that fewer students are taking classics and history, is there any point in pretending we have anything approaching a common culture any more?

Or do we need to know the names? Look at more recent manifestations of Gothic visuals, like Charles Addams, Edward Gorey, Lemony Snickett and Tim Burton. Does it help to know that Fuseli influenced these guys? Indeed, were the influences conscious at all? Or should I just tell you to go and see this exhibition because it's weird and wondrous and one more reason for being in cold, scared London?

Or do we need to know the names? Look at more recent manifestations of Gothic visuals, like Charles Addams, Edward Gorey, Lemony Snickett and Tim Burton. Does it help to know that Fuseli influenced these guys? Indeed, were the influences conscious at all? Or should I just tell you to go and see this exhibition because it's weird and wondrous and one more reason for being in cold, scared London?*Voltaire, Saussure, Jung, Ursula Andress, Yul Brynner

Saturday, February 18, 2006

This is the postmodern world

O, to be in England...

This morning, I sat in a hot, deep bath, reading Paul Whitelaw's Belle and Sebastian biography, listening to Brian Matthew's Sounds of the Sixties on Radio 2 and wondering when he's going to get a better catchphrase than "That's it for this week, see you next week."

At 10 o'clock, he handed over (with his customary hint of disapproval) to Jonathan Ross, who kicked off with The Jam. I eased myself out of the bath, and attempted a Welleroid guitar hero leap while bellowing "Eating trifles! Eating trifles!"

Of course, I fell flat on my soapy arse. But I did feel moderately proud to be British.

This morning, I sat in a hot, deep bath, reading Paul Whitelaw's Belle and Sebastian biography, listening to Brian Matthew's Sounds of the Sixties on Radio 2 and wondering when he's going to get a better catchphrase than "That's it for this week, see you next week."

At 10 o'clock, he handed over (with his customary hint of disapproval) to Jonathan Ross, who kicked off with The Jam. I eased myself out of the bath, and attempted a Welleroid guitar hero leap while bellowing "Eating trifles! Eating trifles!"

Of course, I fell flat on my soapy arse. But I did feel moderately proud to be British.

Friday, February 17, 2006

Don't touch that dial!

Good Night, and Good Luck

Good Night, and Good Luck (Dir: George Clooney, 2005)

Considering Hollywood's supposed crypto-Stalinist bias, it's a little odd that there have been so few movies about McCarthyism. Sure, lots of films have touched on the subject, in the context of the suffocating conformity of the Eisenhower years, but the only one I can recall that plonked the subject in the centre of the action was Martin Ritt's The Front (1976), starring Woody Allen as a cashier who acts as a stooge for the work of blacklisted writers. Now seems as good a time as any to offer a more serious telling of the tale, especially with toxic right-wing fruitcake Ann Coulter telling anyone who'll listen that McCarthy was one of the good guys.

But Good Night, and Good Luck doesn't quite do that. Oh sure, McCarthy's puffy, sweaty face is all over the place, haranguing, sneering, quoting Shakespeare, in contrast with the glacial David Strathairn as Ed Murrow, all etched concern and impassive gazes into the distance. But it's not really a film about witch-hunts.

Because McCarthy isn't portrayed by an actor, the opposition and obstruction that Murrow encounters is presented in the form of his bosses William Paley (Frank Langella) and Sig Mickelson (Jeff Daniels). And their objections aren't based on politics; it's simple economics. "People want to enjoy themselves," says Paley, pointing out that The $64,000 Question raises more ad revenue, at a third of the cost of Murrow's earnest probing. "Did you know that the most trusted man in America is Milton Berle?" asks producer Fred Friendly (George Clooney). Even Murrow knows the score. When told his ratings are good, his response is a rueful "Right up there with Howdy Doody."

Because this movie is essentially about television, and more generally about all mass media. The McCarthy hook is simply a means of showing one way that TV can be used, for the greater good. But even a cathode-ray saint like Murrow is tainted by association with the brutal truth of ratings. When he's not stitching up "the junior Senator from Wisconsin", as McCarthy is regularly described, he's asking Liberace when he's going to get married, colluding in the showbiz smokescreen (and, God, is there a lot of smoke in this movie). Strathairn plays him as stiff, slightly pious, even dull, when compared to the likes of Clooney and Robert Downey, Jr. Only when the TV camera light comes on does he spring into life. He is a creature of TV, with all the good and bad of the medium in his DNA. And he knows that if the punters have to choose an Ed, they'll choose Sullivan, not him.

The format is consciously old-fashioned and self-referential, right down to the quasi-Brechtian use of jazz standards (sung by the magnificent Dianne Reeves) to counterpoint the action. It's shot in black and white, in a clunky flashback format that has the action bookended by Murrow's 1958 speech to his industry colleagues. But when Strathairn points out that, without the diligence and conscience of professionals, television is "merely wires and lights in a box", it's not the cinema having a supercilious dig at television, like some of the movies that responded fearfully to the new medium in the 1950s. After all, the simple fact that this movie is nominated for an Oscar, while the real big box-office monsters aren't, demonstrates that the art/commerce dialectic is buzzing as much on the big screen as it is in TiVoLand. Idiot media has come a long way since Liberace searched for a nice girl to take home to mother - and yet it remains pretty much the same. The keynote of Good Night, and Good Luck is the whole of showbiz looking in on itself, with a deeply Murrowed brow.

Thursday, February 16, 2006

Rat tale

Hear the Wind Sing, by Haruki Murakami (1979)

"Why do you read books?"

"Why do you drink beer?"

This week, I crossed a line. I am no longer just a casual Murakami fanboy who does half-assed things like naming a blog after a quotation from Dance Dance Dance. This week I went onto ebay and ordered a copy of Murakami's first novel, which has never been published outside Japan. God, it felt good, reading this bonsai volume on the Tube, dressed in black, stroking my chin, looking slightly wistful, glad I'd just had my hair cut with appropriate puritan severity.

The legend goes that Murakami was inspired to write fiction at a baseball game, and he knocked this off in a matter of weeks. It's a short, rather formless text, in which an unnamed narrator reflects on his various loves, drinks beer in J's bar, and gets slightly existential with his buddy The Rat. In this way, it forms a thematic whole with the other components of the so-called Rat Trilogy, Pinball 1973 (even harder to get hold of, it would seem) and A Wild Sheep Chase.

As with so many first novels, it's writing about writing. The twist is that it's The Rat, not the narrator, who makes a success of words. The central figure becomes bogged down in analysing the life story of a fictitious author Derek Heartfield, who in 1938 jumped off the Empire State Building carrying an open umbrella. The unspoken irony is that Heartfield sounds like a complete git, and his breathless sci-fi sounds even worse.

Already, many of Murakami's running obsessions are in place. It's a tale of lost, adolescent love, recalled from a position of bourgeois matrimony, as in South of the Border, West of the Sun. There's a physically damaged girl, missing a finger in this case, rather than the limping girl of The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle. There's a suicidal girlfriend (see Norwegian Wood). And his characters, as ever, seem resolutely un-Japanese in their tastes, listening to the Beach Boys and Miles Davis and Beethoven, and eating coldcuts and drinking bourbon. A couple of them even watch The Bridge On The River Kwai, which can't be much fun for Japanese viewers, surely? The only shock for Harukiphiles appears on page 117, when a character refuses a handjob - I think the first and only time this happens in his fictional universe.

It's a slight tale, between appropriately flimsy covers. The translation, by the usually reliable Alfred Birnbaum, occasionally strains for hip American idiom, and ends up sounding like a desperately bourgeois bank manager trying to pull in a hippy commune. The recurring voice of a radio DJ is a particularly grating example. This may be because the intended audience is Japanese learners of English, rather than gaijin readers.

"That's why, seeing as how this cool head would otherwise doze right off into the sludge of time, I keep spurring myself on with beer and cigarettes to write these pages. I take lots of hot showers, shave twice a day, listen to old records over and over again."

So, a minor disappointment, but necessary to see where Haruki-san is really coming from. Now I've just got to track down Pinball 1973 and then I really will be a sad case. But that's crossing another line.

"Why do you read books?"

"Why do you drink beer?"

This week, I crossed a line. I am no longer just a casual Murakami fanboy who does half-assed things like naming a blog after a quotation from Dance Dance Dance. This week I went onto ebay and ordered a copy of Murakami's first novel, which has never been published outside Japan. God, it felt good, reading this bonsai volume on the Tube, dressed in black, stroking my chin, looking slightly wistful, glad I'd just had my hair cut with appropriate puritan severity.

The legend goes that Murakami was inspired to write fiction at a baseball game, and he knocked this off in a matter of weeks. It's a short, rather formless text, in which an unnamed narrator reflects on his various loves, drinks beer in J's bar, and gets slightly existential with his buddy The Rat. In this way, it forms a thematic whole with the other components of the so-called Rat Trilogy, Pinball 1973 (even harder to get hold of, it would seem) and A Wild Sheep Chase.

As with so many first novels, it's writing about writing. The twist is that it's The Rat, not the narrator, who makes a success of words. The central figure becomes bogged down in analysing the life story of a fictitious author Derek Heartfield, who in 1938 jumped off the Empire State Building carrying an open umbrella. The unspoken irony is that Heartfield sounds like a complete git, and his breathless sci-fi sounds even worse.

Already, many of Murakami's running obsessions are in place. It's a tale of lost, adolescent love, recalled from a position of bourgeois matrimony, as in South of the Border, West of the Sun. There's a physically damaged girl, missing a finger in this case, rather than the limping girl of The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle. There's a suicidal girlfriend (see Norwegian Wood). And his characters, as ever, seem resolutely un-Japanese in their tastes, listening to the Beach Boys and Miles Davis and Beethoven, and eating coldcuts and drinking bourbon. A couple of them even watch The Bridge On The River Kwai, which can't be much fun for Japanese viewers, surely? The only shock for Harukiphiles appears on page 117, when a character refuses a handjob - I think the first and only time this happens in his fictional universe.

It's a slight tale, between appropriately flimsy covers. The translation, by the usually reliable Alfred Birnbaum, occasionally strains for hip American idiom, and ends up sounding like a desperately bourgeois bank manager trying to pull in a hippy commune. The recurring voice of a radio DJ is a particularly grating example. This may be because the intended audience is Japanese learners of English, rather than gaijin readers.

"That's why, seeing as how this cool head would otherwise doze right off into the sludge of time, I keep spurring myself on with beer and cigarettes to write these pages. I take lots of hot showers, shave twice a day, listen to old records over and over again."

So, a minor disappointment, but necessary to see where Haruki-san is really coming from. Now I've just got to track down Pinball 1973 and then I really will be a sad case. But that's crossing another line.

Cash + Coldplay

Further thought re: Walk The Line; when we see additional characters such as Jerry Lee Lewis, Elvis Presley etc, represented in a fictional way, do we see them as impersonations of Dennis Quaid, Kurt Russell, etc? Simulacrum City.

Also, overheard at The Brits: "Stop giving James Blunt a hard time. Be proud, he's British." Thus saith boring, bland, posh Chris Martin, leader of bland, posh, boring AOR combo Coldplay, with regard to posh, boring, bland ex-military troubador James Bl(o)unt.

Also, overheard at The Brits: "Stop giving James Blunt a hard time. Be proud, he's British." Thus saith boring, bland, posh Chris Martin, leader of bland, posh, boring AOR combo Coldplay, with regard to posh, boring, bland ex-military troubador James Bl(o)unt.

Wednesday, February 15, 2006

Carluccio's, St Christopher's Place

Yesterday afternoon, identical twin sisters, identically dressed down to glasses and earrings and bright orange hair, ordering exactly the same food. As I pass them, one is speaking French, one is speaking English.

Bangkok is a weird place, but for real David Lynch moments, London is the centre of the universe.

All that was missing was the dwarf.

Bangkok is a weird place, but for real David Lynch moments, London is the centre of the universe.

All that was missing was the dwarf.

Hotter than a pepper sprout

Walk The Line (Dir: James Mangold, 2005)

Walk The Line (Dir: James Mangold, 2005)One of my favourite movies as a kid was The Glenn Miller Story, encouraged by a father who was a big band nut, and a mother for whom Jimmy Stewart was a secular saint. At the age of eight or so, I really believed (or wanted to) that the creative process went something like this:

Helen Miller (aka June Allyson): Say Glenn, that's a pretty tune.

Glenn Miller (Stewart): Oh shucks, Helen, it's just a little something I've been playing around with. I'm thinking of calling it 'Serenade at Moonlight'.

Helen: Why not just call it 'Moonlight Serenade'?

Glenn: Say, that's a swell idea!

The Johnny Cash biopic Walk The Line is forever teetering on the brink of such charming dunderheadedness, but never quite falls over. The closest it comes is when June Carter (Reese Witherspoon) hurls her rage and a few bottles at the pill-popping Cash, berating him because "y'all don't walk no line". Immediately cut to Cash (Joaquin Phoenix) trying out the chords for this li'l ole song he's just done written, and it's called...

But what do you expect when the subject's real life was so melodramatic? Like last year's Ray, Walk The Line suggests that the hero's problems really kicked off with the accidental death of a sibling - in Cash's case, when his brother had his torso ripped open by a rotary saw. The hellraising and pillpopping were just a matter of time. On the way, we get the nervous audition, the fumbles with groupies, the collapse on stage, the love of a good woman returning him to the straight and narrow, etc etc. Apparently certain elements on the swivel-eyed evangelical right have been huffy that the script downplays the role of Christianity in Cash's return to the land of the living. But surely the slightly ludicrous scene where Cash backs his tractor into the river, and emerges from the water into June's loving arms, has enough baptismal oomph to please the holiest roller?

The film pretty much stops at Folsom Prison, so we miss the glorious (Rick Rubin) and unfortunate (Billy Graham) episodes in the great man's later career. However, for all its faults, Walk The Line communicates the smouldering intensity of Cash's stage presence, andf the steely commitment that hid behind Carter's candysweet image. And the performances are magnificent. Witherspoon will get her Oscar, or I'm a rhinestone; Phoenix is Oscar-worthy, but might suffer from some unusually strong competition in the male category.

Meanwhile, I just went out and bought five Johnny Cash CDs. So somebody must be doing something right...

Tuesday, February 14, 2006

Overheard at Oxford Circus tube

"I'm sorry to tell you, the Black Panthers were all assassinated by James VI."

Flipping their lids

The Waking Eyes, Blow Up @ Metro Club, London, 13 Feb 2006

The Waking Eyes, Blow Up @ Metro Club, London, 13 Feb 2006Howling like the bored wind that whips their native Winnipeg, The Waking Eyes slap Beatley harmonies onto Stoogey guitars. Their whole existence seems to have erupted from the bit where Dick Dodd of The Standells yowls "fruuuuustrated women" on their 1966 hit 'Dirty Water'. Funky keyboards and a cool trumpet add texture, but they're fighting a losing battle against the Metro's endearingly ramshackle sonic capabilities.

Image be damned; think Rory Gallagher's head on Angus Young's body, wearing a jacket stolen from a decomposing geology lecturer. It's not the future of rock 'n' roll, but it's a fun seam of the past these guys are mining.

Sunday, February 12, 2006

But we don't want to give you that...

Q & A, by Vikas Swarup (2005)

I used to be a bit of a quiz show groupie, back in the day. Not just the obvious ones (Mastermind, Weakest Link, Brain Of Britain, University Challenge) but forgotten stuff like Win Beadle’s Money and BackDate (with the lovely Valerie Singleton) and Defectors.

However, I’ve never made it onto Who Wants To Be A Millionaire?, which provides the blueprint for the fictional Who Will Win A Billion? (W3B), the show at the heart of Vikas Swarup’s debut. The saga of the disgraced Major Ingram is a clear influence on Swarup’s yarn, but he sensibly opts for a fake show. This avoids the problem that David Nicholls ran into when writing the University Challenge novel Starter For Ten; when the rules of the original show didn’t fit Nicholls’ narrative requirements, he changed them. The fictional show also allows Swarup to concoct a truly loathsome, corrupt host in Prem Kumar. Since the Indian edition was hosted by national treasure Amitabh Bachchan, a fictional show is the only means by which he could have made the presenter so venal.

Most quizzers and trivia junkies will tell you that the most annoying question they get from non-addicts is the incredulous “How the hell do you know that?”; the problem being that, most of the time, we don’t know. It’s just kinda there. Swarup’s hero, Ram Mohammed Thomas (whose multicultural name offers a microcosm of his rootless upbringing) knows exactly how he came by each answer as he climbs each level towards his goal of a billion rupees, and these experiences provide the meat of the story.

The structure, with the hero recounting his picaresque story to a benevolent authority figure, owes something to The Life Of Pi, and there’s a nagging doubt as to whether Ram Mohammed is a similarly unreliable narrator. In the event, Swarup turns out to be playing a straight hand, without any self-consciously po-mo tricks. Everything is rounded up a little too neatly at the end, possibly in a conscious nod to the structure of the Bollywood movies that provide numerous points of reference; there’s one unlikely revelation of identity at the end that will have most Western readers snorting with derision.

But a more respectable model is Dickens. Swarup’s goodies either triumph, or perish in an appropriately pathetic, tearjerking, Smike-like manner. The baddies face destruction, or at best, humiliation. But the more deep seated evil remains in place. Indeed, the depiction of the sheer bloody unfairness of Indian society is unrelenting. The police are corrupt and brutal; teachers, parents and priests are exploiters and abusers worthy of Dotheboys Hall; the TV company behind W3B is as filthy as a Mumbai sewer. Movie heroes, when they step off the screen, are empty shells or fraudulent perverts. Waiters, maids and whores, by contrast, are paragons of humble decency. What’s more surprising is that the author is a successful Indian diplomat in his day job, but reserves his most vicious contempt for the ‘haves’ of his country.

Q & A breaks little literary ground, but it does offer a resonant, entertaining trawl through the underside of a billion-strong society. The Bollywood version, inevitably, is imminent.

I used to be a bit of a quiz show groupie, back in the day. Not just the obvious ones (Mastermind, Weakest Link, Brain Of Britain, University Challenge) but forgotten stuff like Win Beadle’s Money and BackDate (with the lovely Valerie Singleton) and Defectors.

However, I’ve never made it onto Who Wants To Be A Millionaire?, which provides the blueprint for the fictional Who Will Win A Billion? (W3B), the show at the heart of Vikas Swarup’s debut. The saga of the disgraced Major Ingram is a clear influence on Swarup’s yarn, but he sensibly opts for a fake show. This avoids the problem that David Nicholls ran into when writing the University Challenge novel Starter For Ten; when the rules of the original show didn’t fit Nicholls’ narrative requirements, he changed them. The fictional show also allows Swarup to concoct a truly loathsome, corrupt host in Prem Kumar. Since the Indian edition was hosted by national treasure Amitabh Bachchan, a fictional show is the only means by which he could have made the presenter so venal.

Most quizzers and trivia junkies will tell you that the most annoying question they get from non-addicts is the incredulous “How the hell do you know that?”; the problem being that, most of the time, we don’t know. It’s just kinda there. Swarup’s hero, Ram Mohammed Thomas (whose multicultural name offers a microcosm of his rootless upbringing) knows exactly how he came by each answer as he climbs each level towards his goal of a billion rupees, and these experiences provide the meat of the story.

The structure, with the hero recounting his picaresque story to a benevolent authority figure, owes something to The Life Of Pi, and there’s a nagging doubt as to whether Ram Mohammed is a similarly unreliable narrator. In the event, Swarup turns out to be playing a straight hand, without any self-consciously po-mo tricks. Everything is rounded up a little too neatly at the end, possibly in a conscious nod to the structure of the Bollywood movies that provide numerous points of reference; there’s one unlikely revelation of identity at the end that will have most Western readers snorting with derision.

But a more respectable model is Dickens. Swarup’s goodies either triumph, or perish in an appropriately pathetic, tearjerking, Smike-like manner. The baddies face destruction, or at best, humiliation. But the more deep seated evil remains in place. Indeed, the depiction of the sheer bloody unfairness of Indian society is unrelenting. The police are corrupt and brutal; teachers, parents and priests are exploiters and abusers worthy of Dotheboys Hall; the TV company behind W3B is as filthy as a Mumbai sewer. Movie heroes, when they step off the screen, are empty shells or fraudulent perverts. Waiters, maids and whores, by contrast, are paragons of humble decency. What’s more surprising is that the author is a successful Indian diplomat in his day job, but reserves his most vicious contempt for the ‘haves’ of his country.

Q & A breaks little literary ground, but it does offer a resonant, entertaining trawl through the underside of a billion-strong society. The Bollywood version, inevitably, is imminent.

Friday, February 10, 2006

The beautiful game

At Fratton Park there's a guy who plays the trumpet, and everyone thinks he's terribly wacky and eccentric. They obviously ain't seen these.

Entirely unconnected, this crap e-fit story made me laugh, as did the news that snogging causes meningitis, which sounds remarkably similar to Victorian fulminations against self-pleasuring.

I'm going back to London for a week (Sunday-Saturday). What should I do when I'm there? Ideas gratefully, etc, etc.

Entirely unconnected, this crap e-fit story made me laugh, as did the news that snogging causes meningitis, which sounds remarkably similar to Victorian fulminations against self-pleasuring.

I'm going back to London for a week (Sunday-Saturday). What should I do when I'm there? Ideas gratefully, etc, etc.

Thursday, February 09, 2006

Flowered up

Broken Flowers (Dir: Jim Jarmusch, 2005)

Broken Flowers (Dir: Jim Jarmusch, 2005)Bill Murray and Jim Jarmusch have been offering pretty similar schtick in recent years, so there's a sense of inevitability that these behemoths of slightly-maladjusted masculinity should bump heads at some stage. And to say the result is a bit disappointing is, perversely, rather what you'd expect and desire.

The plot, as it is, is simple. Murray's Don Johnston ("with a 'T'") is a materially successful, emotionally vacant man with a big television and a fine collection of Fred Perry leisurewear. His girlfriend (Julie Delpy) leaves him just as he receives a letter purporting to be from an unidentified ex-girlfriend, informing him that he has a 19-year-old son. His neighbour Winston (Jeffrey Wright) persuades him to track down his former lovers. So he does.

It doesn't warrant a SPOILER ALERT if I inform you that Don's quest is unsuccessful. More importantly (and more Jarmuschian), he doesn't "learn something about himself" either. He just drives and flies around, reacquainting himself with his exes, with varying levels of embarrassment and violence. And then he comes home, to his empty house and his big telly. There are a couple of encounters, one awkward, one utterly fleeting, with young men who might be... maybe... but almost certainly aren't.

This is chamber Jarmusch, a small film. Don never faces danger, beyond a punch from a possessive redneck, and a supercilious look from Chloe Sevigny. There's no equivalent of the wilderness that envelops Johnny Depp in Dead Man, or the urban corruption that Forest Whittaker faces in Ghost Dog. If Don has any cinematic antecedents, it's the suburban schnooks that Jack Lemmon used to play, or maybe Kevin Spacey's Lester Burnham.

Bill Murray, of course, does his Bill Murray thing, with that Bill Murray face that he uses whether he's falling for Scarlett Johansson or zapping ghosts. He offers no surprises to anyone who's been inside a cinema in the last 20 years, but in his own, tired way, he communicates as much as a closing line from Beckett. Although Krapp never boasted such a spiffy line in Fred Perry tracksuits.

While we're in Jarmuschland, this week I finally got round to watching In The Soup (Dir: Alexandre Rockwell, 1992), in which J.J. makes a brief appearance. The movie's most lasting claim to historical notoriety is that it won the Grand Jury Prize at Sundance in '92, edging out a little gangster flick called Reservoir Dogs.

While we're in Jarmuschland, this week I finally got round to watching In The Soup (Dir: Alexandre Rockwell, 1992), in which J.J. makes a brief appearance. The movie's most lasting claim to historical notoriety is that it won the Grand Jury Prize at Sundance in '92, edging out a little gangster flick called Reservoir Dogs.Ominously, it's the tale of a frustrated NYC moviemaker called Adolpho Rollo, played by Steve Buscemi. Already the alarm bells are going; you can hear the film-school tutor saying "Write about what you know..." Rockwell and his alter ego even share the same initials. Help.

Actually, it's not that bad. Adolpho gets caught up in the schemes of the overbearing Joe (the magnificent Seymour Cassel), who's prepared to finance his hysterically-atrocious-sounding flick with the proceeds of numerous dodgy deals. The problem is, Adolpho is expected to help out in the scams, which culminate in a drug deal involving a dwarf and a man in a gorilla suit.

So far, so indie-schmindie. Now, retrospect is a fine thing, but it's hard to see what got the jury so excited over this, rather than Q.T.'s little outing. It's all just so student-filmy, with sequences thrown in clinically to appeal to cinephiles and ironic chin-strokers; most egregious being the pillow fight, a la Zero de Conduite. And when, at the end, Adolpho suggests to Joe, "Let's make a film about us!" it feels like the jump-the-shark moment in a tired sitcom, when the writers suddenly decide to get all self-referential. Metafiction for Dummies, anyone? And surely we've all realised how lazy the "dwarf=weirdness" trope has become after Peter Dinklage's rant in the rather better Steve-Buscemi-tries-to-make-a-movie movie Living In Oblivion.

On the plus side, the acting is mostly good (although Jennifer Beals as the object of Adolpho's frustrated yearning has a touch of "I'm the director's wife, btw" about her). But the whole enterprise is summed up by the fact that the movie was shot in colour, then converted to mono. Which, presumably, was enough to satisfy the great and the good at Sundance of its indie credentials, but didn't hack it in the wider world.

Wednesday, February 08, 2006

Great first lines

Just posted this in a first line discussion on This Space. Not just a first line, but a first line of a first book:

"In Melton Mowbray in 1875 at an auction of articles of 'curiosity and worth', my great-grandfather, in the company of M his friend, bid for the penis of Captain Nicholls who died in Horsemonger jail in 1873."

Ian McEwan, 'Solid Geometry', from First Love, Last Rites

Can anyone beat that for a debut?

(Update, Feb 9: go here for more.)

"In Melton Mowbray in 1875 at an auction of articles of 'curiosity and worth', my great-grandfather, in the company of M his friend, bid for the penis of Captain Nicholls who died in Horsemonger jail in 1873."

Ian McEwan, 'Solid Geometry', from First Love, Last Rites

Can anyone beat that for a debut?

(Update, Feb 9: go here for more.)

Dead reckoning

News that the terminally-ill theatre director Peter Halasz is to stage his own funeral while still alive prompts one of those unattainable fantasies. Who'd turn up? Will they cry? Will they laugh? Will they yawn? Will they nibble dry ham sandwiches and make uncomfortable small talk, then get home in time for Countdown?

All I know is, I want Johnny Cash playing when I go. 'Ghost Riders In The Sky' as I'm consumed by the flames, and 'We'll Meet Again' as the multitudes troop out, sniffing softly, wondering who'll be in Dictionary Corner on the other side.

All I know is, I want Johnny Cash playing when I go. 'Ghost Riders In The Sky' as I'm consumed by the flames, and 'We'll Meet Again' as the multitudes troop out, sniffing softly, wondering who'll be in Dictionary Corner on the other side.

Tuesday, February 07, 2006

Taking a Ba'ath

David Cerny's installation of Saddam in formaldehyde has been banned from display in the Belgian town of Middlekerke.

David Cerny's installation of Saddam in formaldehyde has been banned from display in the Belgian town of Middlekerke.But who's it meant to offend? Muslims? Ba'athists? Brian Sewell? What with the cartoon rumpus, and following so soon after Tate Britain bottled it with regard to John Latham's God Is Great, it seems that the self-appointed guardians of our aesthetic wellbeing are running around like, well, bisected cows.

I was going to do all the London galleries next week. By the time I get there, will there be anything left?

Got me on my knees...

This weekend I picked up Reprise! When jazz meets pop, a mixed-bag compilation CD of jazz (Wes Montgomery, Brad Meldhau) and jazz(ish) (Jamie Cullum, Bobby McFerrin) musicians covering rock songs (Madonna, Hendrix, Radiohead, Bowie...) Some are good: Herbie Hancock finds the fingersnapping potential that Kurt missed in 'All Apologies'; the delicious Senor Coconut shows that some jokes have legs, hitting Deep Purple square in the castanets. Some are middling; and then there's Joshua Redman. The saxophonist pulls off the prodigious feat of turning in a muzak version of 'Tears In Heaven' even more grotesque and emetic than the one perpetrated by its originator, Eric Clapton.

This weekend I picked up Reprise! When jazz meets pop, a mixed-bag compilation CD of jazz (Wes Montgomery, Brad Meldhau) and jazz(ish) (Jamie Cullum, Bobby McFerrin) musicians covering rock songs (Madonna, Hendrix, Radiohead, Bowie...) Some are good: Herbie Hancock finds the fingersnapping potential that Kurt missed in 'All Apologies'; the delicious Senor Coconut shows that some jokes have legs, hitting Deep Purple square in the castanets. Some are middling; and then there's Joshua Redman. The saxophonist pulls off the prodigious feat of turning in a muzak version of 'Tears In Heaven' even more grotesque and emetic than the one perpetrated by its originator, Eric Clapton.But of course, you're not allowed to say that are you? Because 'Tears In Heaven' was precipitated by a personal tragedy, so whenever EC picks up his trusty acoustic, we're supposed to think about how sad it was that his son fell out of that window, and forget what a bland sap the man once known as "God" has become.

Time was when Clapton transmuted his personal tragedies and traumas (drug addiction; forbidden love for his best friend's wife; being Caucasian) into songs of genuine passion, power and imagination. It's easy to forget what an innovator he was, looking at the anaemic dullard he's become, boring, performing pale blues for paler people. But that's about as popular a sentiment as arguing that Princess Diana was a slightly dim serial shagger with a martyr complex; or that the World Trade Center was an architectural abomination.

Just compare the ache of the original version of 'Layla' with his Unplugged take. E.C. (C.B.E.) now sounds like George Formby feeling a wee bit melancholy, backed by a Chas 'n' Dave tribute band. But then, real tragedy always contains a drizzle of farce.

Monday, February 06, 2006

Neverland

Never Let Me Go, by Kazuo Ishiguro (2005)

Never Let Me Go, by Kazuo Ishiguro (2005)I seem to remember that when The Remains Of The Day came out, some critic or other remarked that it was nice to see a sensible novel, what with all this silly magic realism going around. I don't know why it was considered so remarkable that Kazuo Ishiguro was writing books without flying carpets in them; maybe it was simply because he was called Kazuo, and not Julian or Martin. It's the same sloppy thinking that gets him placed in the 'Asian Fiction' section of my local bookshop. Despite being born in Nagasaki, Ishiguro is very English, and his latest novel begins in that most English of settings, a public school. (Go here for an explanation of the perversely misleading British expression, if needs be.)

In fact, it doesn't quite begin there - the description of the school is framed as a flashback, so the immediate implication is that we're embarking on that current fave, the Friends Reunited narrative - see Jonathan Coe's The Closed Circle, the TV series "40", and back to Frederic Raphael's The Glittering Prizes - even, perhaps, to Brideshead Revisited. But pretty soon we realise this isn't Jennings or even Harry Potter. The children are known by forenames and initials - Kathy H., Tommy D. Shades of Josef K.? There are no teachers, just "guardians". Parents are never mentioned, and nobody seems to go home. And what are donors, and carers? And why do these kids seem to spend all their time doing art and PE?

There's a mystery underpinning the narrative, and Ishiguro lets it seep out almost casually. He's aided by the Bildungsroman structure; the narrator, Kathy, comes to realise her ultimate destiny with a realistically childlike sense of inevitability, the same way that the non-existence of Santa Claus comes as a gradual awareness, rather than a brutal shock. (Incidentally, readers of the US paperback edition will have had their sense of shock at plot developments tempered even further by the comically po-faced Library of Congress catalogue listing at the front, which treats works of fiction like junior high text books. Let's just say that The Wasp Factory would receive something like "1. Scotland--Fiction. 2. Setting fire to insects--Fiction. 3. Oh, by the way, the narrator's a girl, did I mention that?--Fiction.")

As the narrative develops, we realise that we're in the realms of Brave New World or Soylent Green, but the sheer acquiescence with which characters accept their cog-like roles makes matters even more chilling. The world he creates is so close to our own ("England, late 1990s", he says; Norfolk, Littlehampton, Oxfam shops, Walkmans), so distant from Huxley's glassy sci-fi.

Ishiguro doesn't do polemical messages, but there is clearly something here about the necessary sacrifice of individuals - "poor creatures", as one character puts it - for the collective good, and the moral quandaries that arise from that. But, most importantly is the disconcerting calm of his characters, and the acceptance of what the reader sees as weird, freakish, unreal. He's done what seemed highly unlikely in 1989, and crafted a very English fragment of magic realism.

The subtitle cringe

As Peter Preston puts it in today's Graun, "Would Ang Lee's Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon have taken the prize if its stars had been forced to speak Chinglish?"

As Peter Preston puts it in today's Graun, "Would Ang Lee's Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon have taken the prize if its stars had been forced to speak Chinglish?"Fair point. But surely either (subtitles or actors forced to speak phonetically from idiot boards), is preferable to dubbing. If you ever have the chance, try to get hold of a Hollywood blockbuster dubbed into Thai. There seems to be one male actor who does all Thai voiceovers, and he sounds like a butch lesbian in a bad mood, whether he's trying to be Tom Cruise, Morgan Freeman or Rupert Everett.

Tieland

Sunday, February 05, 2006

Mutually Assured Bullshit

"You could go around implying you'd read all kinds of things, nodding knowingly when someone mentioned, say, War and Peace, and the understanding was that nobody would scrutinise your claim too rationally."

Kazuo Ishiguro, Never Let Me Go

Kazuo Ishiguro, Never Let Me Go

Saturday, February 04, 2006

Dance x 3

In case anybody's wondering about the origin of the title of this blog...

"The assignment was a piece called "Good Eating in Hakodate" for a women's magazine. A photographer and I were to visit a few restaurants. I'd write the story up, he'd supply the photos, for a total of five pages. Well, somebody's got to write these things. And the same can be said for collecting garbage and shoveling snow. It doesn't matter whether you like it or not - a job's a job. For three and a half years, I'd been making this kind of contribution to society. Shovelling snow. You know, cultural snow."

Haruki Murakami, Dance Dance Dance

"The assignment was a piece called "Good Eating in Hakodate" for a women's magazine. A photographer and I were to visit a few restaurants. I'd write the story up, he'd supply the photos, for a total of five pages. Well, somebody's got to write these things. And the same can be said for collecting garbage and shoveling snow. It doesn't matter whether you like it or not - a job's a job. For three and a half years, I'd been making this kind of contribution to society. Shovelling snow. You know, cultural snow."

Haruki Murakami, Dance Dance Dance

Friday, February 03, 2006

Prophet margins

More, more and yet more stuff about bad cartoons that nobody likes, but for different reasons. And here's some more, if you want it.

More, more and yet more stuff about bad cartoons that nobody likes, but for different reasons. And here's some more, if you want it.Meanwhile, the UK Government arses up its own religious hatred bill; and BNP Reichsfuhrer Griffin and his weasel-eyed catamite are let off on charges of... well, being unpleasant, really...

Some have accused the BBC of double standards for not showing the cartoons, despite having shown Jerry Springer: The Opera and thus offending Christians. Others have said that those defending the right to publish the cartoons would not have defended Der Sturmer's anti-semitic outpourings. But we're talking different kinds of horrid.

The problem with Der Sturmer and similar propaganda was that it sought to incite hatred against Jews. That's the same argument used against the BNP duo. However, the reason people in the West are edgy about the danish cartoons is subtly different. It's less to do with stirring up hatred against Muslims - freedom of speech trumps that one, except in George Galloway's house. It's more about the worry that the pictures will provoke Muslims into reciprocal acts of hatred against the West.

And, as several Islamic commentators have argued, if the desire of the cartoonists was to provoke Muslims into violence, they've succeeded. D'oh. "The protests in the Middle East have proven that the cartoonist was right," said Tarek Fatah, a director of the Muslim Canadian Congress. "It's falling straight into that trap of being depicted as a violent people and proving the point that, yes, we are." Safiyyah Ally at altmuslim.com takes a similar line, suggesting “We haven't learned from the Rushdie affair - this is yet another instance where we've gone out of our way to make ourselves look stupid.”

Oh, and that thing they were doing in Jerry Springer? It's called taking the piss. That’s all.

“Oh, the Protestants hate the Catholics,

And the Catholics hate the Protestants,

And the Hindus hate the Moslems,

And everybody hates the Jews.”

Tom Lehrer, ‘National Brotherhood Week’

Shooting people for profit and pleasure

Branded To Kill/Koroshi no rakuin (Dir: Seijun Suzuki, 1967)

Branded To Kill/Koroshi no rakuin (Dir: Seijun Suzuki, 1967)No sooner do I argue that Asians are environmentally hardwired to see the world differently from the way us barbaric gaijin see it, this movie comes along to prove it. Thanks to James Lander, the coolest chemical engineer in the known world, for pointing me to a frenetic yakuza thriller from one of Mr Tarantino’s favourite directors.

The back story goes some way to explaining the end results. Suzuki had got on the tits of his studio, Nikkatsu, by making insanely garish slabs of psycho-Zen weirdness (like Tokyo Drifter) rather than the sushi-cutter shoot-em-ups the Osaka bourgeoisie demanded. So they gave him one last chance; here’s the script, here’s the star, here’s the budget and you’re doing it in mono.

The brilliance is that Suzuki did exactly what he was told. He just took the raw ingredients and gave them a little wasabi on top. The plot is negligible; Hanada, the third-best sniper in Japan (played by fugu-faced Jo Shishido), screws up a hit when a butterfly (lusciously fake) lands on his rifle, and his paymasters turn on him. This leads to a confrontation with the No. 1 killer, with predictably messy results.

So what do we get on top? Well, an anti-hero who can only get the horn when he sniffs freshly cooked rice for a start, after which he pleasures his squealing girlfriend every which way, including halfway up a spiral staircase. Add to the bubbling chanko-nabe: a spot of torture by flamethrower; dead birds as dashboard accessories; diamonds inside glass eyes; execution by faulty plumbing; a strangely homoerotic toilet routine; the coolest Morris Minor stunts you’ve ever experienced; and you’ve got one magnificently strange movie. Too strange, too magnificent for Suzuki’s bosses, who fired him after this final outrage. Oops.

It's all beautifully cool and deadpan, with a central figure who's rather more anti than hero, and a delicious streak of sadism that keeps the viewer from relaxing too much into ironic-chortle mode. It would be pointless to identify the influences at work here, and then to distinguish them from the movies that Branded To Kill has influenced in turn. Let’s just be dogmatically postmodernist and suggest that the only difference between the two groups is an accident of chronology. So sniff the rice long enough and you’ll find befores and afters: A Bout De Souffle; Reservoir Dogs; Point Blank; The Killer; Get Carter; High Noon; Leon; Ashes and Diamonds; The Defiant Ones; Le Samourai; The Passion Of Joan Of Arc; Grosse Pointe Blank; Tampopo (for the food fetishism); and The Prisoner, both for the way key characters are broken down into numerical signifiers, and for the final, doomed, triumphant “I am Number One!”

Expect a bad remake, starring Matt Damon, any day soon.

Beyond Liff

Concepts for which there are no words. An occasional series.

1. The vibration you feel in your fingers while typing on a laptop at the same time as a CD of the Second Brandenburg Concerto is playing within.

1. The vibration you feel in your fingers while typing on a laptop at the same time as a CD of the Second Brandenburg Concerto is playing within.

Thursday, February 02, 2006

RIP Black Type

Smash Hits has been taken to the vet for the last time.

Smash Hits has been taken to the vet for the last time.Yeah, I know, it had been dreadful for years. Remember that Emma Jones woman on Question Time? And I blush at the fact that I applied for jobs there more than once.

But in the early 80s, when Neil Tennant was on board, it was funny and subversive, like an entry-level NME. (Which was also funny and subversive at the time, if you recall.)

Oh, and Moira Shearer died. If Smash Hits had been around at the time, she'd probably have been on every third cover between 1947 and 1952. The Christina Aguilera of her day. Or something.

Might watch The Red Shoes later.

Hysteria 1, Art 0

The Muhammad cartoons row rumbles on; now they've appeared in France Soir.

In all the arguments about freedom of speech and reckless intent to provoke, nobody's pointed out the most salient point about these daubings.

They're really very bad.

In all the arguments about freedom of speech and reckless intent to provoke, nobody's pointed out the most salient point about these daubings.

They're really very bad.

Wednesday, February 01, 2006

It's the Cultural Bathos Generator!!!!

From an idea by Small Boo.

From an idea by Small Boo."I really like jazz, especially Kenny G."

"I'm heavily into philosophy. I've read everything Paulo Coelho's written."

"I go to the theatre whenever I can. Did you see We Will Rock You? Great, wasn't it?"

"I'm trying to get into opera. Which album should I buy - Il Divo or G4?"

Feel free to add your own.

Have I the right?

For those who don’t know, or don't care, or are too young, or otherwise remain emotionally unaffected by the news that Tom Baker is to be the new voice of BT text messages, the title is a reference to Genesis of the Daleks. The Doctor has the opportunity to wipe out the embryonic Daleks, thus preventing misery and enslavement for millions. But… might there not be some good that might come out of the evil? Is such a decision really so straightforward? When I first saw this, my seven-year-old self realised that very few big ideas could exist with no shades of grey whatsoever.

For those who don’t know, or don't care, or are too young, or otherwise remain emotionally unaffected by the news that Tom Baker is to be the new voice of BT text messages, the title is a reference to Genesis of the Daleks. The Doctor has the opportunity to wipe out the embryonic Daleks, thus preventing misery and enslavement for millions. But… might there not be some good that might come out of the evil? Is such a decision really so straightforward? When I first saw this, my seven-year-old self realised that very few big ideas could exist with no shades of grey whatsoever.I strongly suspect that Bush, Blair and Osama were doing something else at the time. Maybe The Bionic Woman was on the other side.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)