Back in the bad old days before I let blogging into my life (let me hear you say

"Amen!"), I used to hover around the

Guardian Talk site. I remember one day, a regular poster mentioned that another poster was ill, and might appreciate good wishes. Good wishes were forthcoming, as they generally were on that site provided you stayed off any subject relating to the Middle East. It transpired that the poster's illness was more severe than was at first suspected; she had cancer; she had good days and bad days; over the next few months, the bad outnumbered the good, and she died.

Sometimes she would post, keeping us in touch with her victories and setbacks; as time went on, she became too tired, and updates came from her daughter, partner, and other people who knew her in the real world. Two things were interesting about the thread: apart from those irregular updates, it needed very little input from the real world, as I reckon at least 90% of the volume came from people who never knew the woman, or even her real name; and, after she died, there was a great deal of pressure on the administrators to keep the thread up in perpetuity. When this was refused (it had swelled to over 10,000 posts, and was slowing down the server), a number of posters archived the whole thing, and circulated it to whoever wanted it.

This is a constant theme when anyone's contrasting web-specific content with old media, and I've had polite disagreements with

Patroclus about it in the past. People love the interactivity, the immediacy, the sense of community, the [

insert your own Web 2.0 buzzword] in blogs, message boards and the like; but when a particular fragment of the web gets serious or significant or famous or infamous, there's immediate pressure to turn it into a book or a film or some other facet of the BBL (Before

Berners-Lee) universe. Part of the reason is that it's still disproportionately difficult to make cash out of a Web product that doesn't involve the sweatier regions of human anatomy; but there's also a sense that a website isn't quite appropriate enough,

permanent enough to mark what really matters.

This appears to be the story behind

Train Man (Densha Otoko). Apparently, the story began in March, 2004, when a young man in Tokyo posted on a chat forum. He'd tussled with a drunk who'd been annoying some women on a train. One of the women sent him some posh teacups as a thank-you present. The young man wondered if this might be a sign that his existence as a virginal

otaku might be coming to an end. He asked the other posters, most of them similarly inexperienced in life beyond manga and IT, for help; and kept them in touch with his slowly (they don't snog until page 334) developing relationship.

It's not a great book, although it does remind us that, however much some East Asian urban cultures have adopted the trappings of the West, Nice Girls still Don't (or, more precisely, if they do, they don't talk about it). The format is fun, with some extraordinary ASCII pics apparently lifted from the forum; but there's very little that wasn't done by, say, Matt Beaumont's

E, or even the 18th-century epistolary novels of

Richardson and

Laclos.

What is interesting is the way the original thread ballooned into a book, a TV show, a play, several

manga and a

movie. (The latter, in gloriously metafictional move, has the girl, Hermès, played by

the actress that she is supposed to resemble in the book.) It's as if a good story would be wasted if it were left to languish online. Only when it's between covers (of a book or a DVD case) is it worthwhile. The fact that this means somebody's making money out of it apparently adds to the validity of the whole thing.

And the fact that somebody's doing that (the nominal author, Nakano Hitori, translates as

"one of us") raises a few more questions. Who holds the copyright on the content of chat forums? Is it jointly owned by the posters, or sucked up by the hosts. The mystery of the whole tale (the protagonists have not come forward) and of the people who nursemaided its transition into other media, add to the confusion.

And then, of course, there's the whole issue of veracity. The

James Frey controversy has raised a number of questions about the intersection between non-fiction, fiction and

"based on a true story"; but again, this one has been rumbling at least since Truman Capote unleashed the

non-fiction novel on us. Whatever the reality, the author (Compiler? Editor? Transcriber? Collector? Cutter-and-paster? Do we need a new terminology for this? I know

"the author" is dead, but...) makes the distinction all but irrelevant, by making the characters so bland and two-dimensional that their own mothers wouldn't recognise them.

So, despite all the precedents, maybe

"one of us" has managed to create a new form of literature. It's something so bland, so undefined, that anybody can take it and apply it to his or her own life. It's the raw material of a fiction, that can be cooked up into something interesting by the participants. Get him to do this, do that. Tell her you love her. Don't tell her. Has she got a sister? Oh no she isn't! Behind you!

In short, it's got all the potential to be a fully interactive narrative. Which is what it was to start with (whether it was

"real" or not), until someone had the bright idea of fixing it into a fairly ordinary book, like a mediocre mosquito, immortalised in amber. What was the point of that?

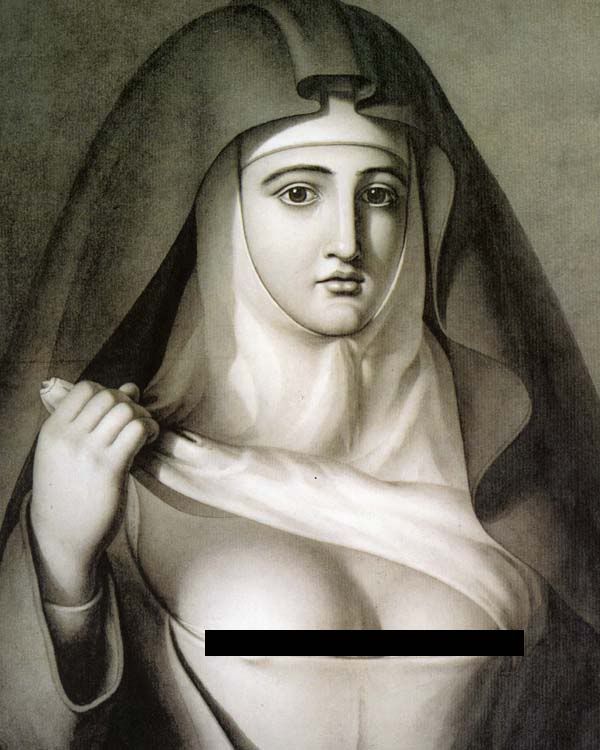

Many people have equated religious fervour with the buzz that one might get from sex, drugs, rock and/or roll (delete as appropriate). The whole career of, for example, Marvin Gaye was an attempt to balance their conflicting, yet strangely similar demands. Alternatively, think of the homoerotic cult of St Sebastian, or saucy Hindu art. But, of course, religious people tend not to admit this, because it might involve the painful acknowledgement that they actually possess genitalia. I remember being dumbfounded to discover that the Ayatollah Khomeini was married with kids. Urrggghh... he did it! And so did Ian Paisley! The Catholic Church's objections to The Da Vinci Code aren't about its suggestions that the institution is packed with mad, corrupt murderers; it's the idea that Jesus might have given a little too much of God's love to Mary Magdalene (or Monica Bellucci, as I like to think of her).

Many people have equated religious fervour with the buzz that one might get from sex, drugs, rock and/or roll (delete as appropriate). The whole career of, for example, Marvin Gaye was an attempt to balance their conflicting, yet strangely similar demands. Alternatively, think of the homoerotic cult of St Sebastian, or saucy Hindu art. But, of course, religious people tend not to admit this, because it might involve the painful acknowledgement that they actually possess genitalia. I remember being dumbfounded to discover that the Ayatollah Khomeini was married with kids. Urrggghh... he did it! And so did Ian Paisley! The Catholic Church's objections to The Da Vinci Code aren't about its suggestions that the institution is packed with mad, corrupt murderers; it's the idea that Jesus might have given a little too much of God's love to Mary Magdalene (or Monica Bellucci, as I like to think of her).