Just as it happened 35 or so years ago, while I watched Johnny Marr’s Glastonbury set I gawped at his dexterity, musical imagination, effortless cool and implausible absence of body fat. Of course, in 1983 his serviceable singing didn’t come into the equation, because someone else was handling those duties.

Ah, yes, Mr Morrissey. What started out (apparently) as arch, subversive flirtation with the trappings and iconography of the far right has tipped right over the edge into full-on Faragerie and worse. He is, officially, no longer charming, and people are lining up either to agonise over the delight they once took in him and his mots (bon and mauvais alike), or to crow that they never liked the preening bigot in the first place. I’m in the first camp, but I guess you’d worked that out already.

So, when Marr trawls through his old band’s songbook, what reaction should we expect from the woke crowd? Awkward shoe-gazing? A mass turning of backs? A petition on change.org? Or ecstatic bellowing along from thousands of sunburned people who know all the words and the B-sides and probably the messages etched on the inner grooves as well, which contrasts with the polite response accorded to the guitar hero’s own solo work. (Note to self: remember that in the real world, Smiths fans always resembled the rowdy lads on the inside of the Rank gatefold more than they did Alain Delon or even Yootha Joyce.) Hate the singer – or at least express disappointment in how he turned out – while still loving the songs; that would appear to be the best option. Of course, the spirit of Morrissey still lingers over everything Marr does; at once there and not there, Schrödinger’s lyricist, Banquo at the vegan feast. This was meant to be a blog post about Johnny, but it’s not, is it?

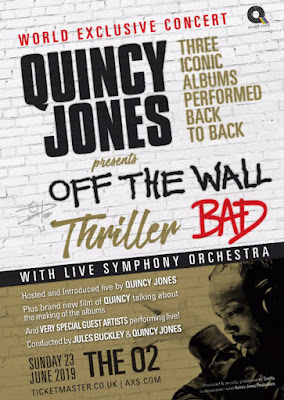

The singer/song divide does appear to be an increasingly popular tactic, whether it’s Quincy Jones playing lots of Michael Jackson songs without ever mentioning Michael Jackson, or Nick Cave’s calm response to the misdeeds of Morrissey himself:

I think perhaps it would be helpful to you if you saw the proprietorship of a song in a different way. Personally, when I write a song and release it to the public, I feel it stops being my song. It has been offered up to my audience and they, if they care to, take possession of that song and become its custodian. The integrity of the song now rests not with the artist, but with the listener.Which, the two or three loyal readers of this blog will know, is pretty much what Roland Barthes (a French theorist who never heard the Smiths but died a beautifully Morrisseyesque death) argued in The Death of the Author. As soon as the author publishes, or releases, or presses “SEND”, he or she leaves the party. I’ve often deployed this as a critical get-out clause; for example in my book about Radiohead’s OK Computer (all good bookshops, etc), I pointed out that the fact Thom Yorke hasn’t read Philip K Dick’s Valis, or can’t remember that the poem that inspired ‘Subterranean Homesick Alien’ was by Craig Raine, doesn’t invalidate those works’ relevance to consideration of his own music. I never thought it would also allow us to skip gaily over the sexual or political misdemeanours of our fallen idols, and I doubt old Roland did either – which rather proves his point, doesn’t it?