Two more contributions to the canon discussion, here as placeholders if nothing else. First, Alexandra Wilson upends Bourdieu by arguing that it’s popular, not classical music than holds all the cultural capital:

Since the 1980s, the media has determinedly and relentlessly painted classical music as “elitist”, boring and old-fashioned. Even Arts Council England, hell-bent on a programme of radical “change” to the cultural landscape, can scarcely conceal its contempt for it. None of this is suggestive of a society in which classical music reigns supreme. It isn’t brave to say you hate classical music so much as bog-standard normal. State publicly that you don’t like classical music, and you’re cool, funny and “relatable”. State publicly that you don’t like popular music, and you’re a weirdo or a snob.

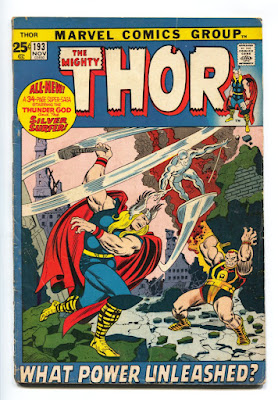

And in the New Yorker, Stephanie Burt defends Penguin’s decision to define Marvel comics and their ilk as classics:

Stories become classics when generations of readers sort through them, talk about them, imitate them, and recommend them. In this case, baby boomers read them when they débuted, Gen X-ers grew up with their sequels, and millennials encountered them through Marvel movies. Each generation of fans—initially fanboys, increasingly fangirls, and these days nonbinary fans, too—found new ways not just to read the comics but to use them. That’s how canons form. Amateurs and professionals, over decades, come to something like consensus about which books matter and why—or else they love to argue about it, and we get to follow the arguments. Canons rise and fall, gain works and lose others, when one generation of people with the power to publish, teach, and edit diverges from the one before.

1 comment:

A fine combination of classic and comic is MArtin Rowson's graphic novel The Waste Land, involving a p.i. trying to find out what's going on in the poem. I think Rowson tried to quote the whole poem directly in the story, but Faber wouldn't let him.

Post a Comment